Half of Jau

LIRE

A former soldier had retired to the village after having served the king for a long time. Seeing himself quite close to his end, he commanded his two sons not to call a bailiff or prosecutor to dispose of his inheritance.

– These cats would cheat you, he told them. It is better to settle between brothers. That is easy, since each of you is entitled to half of everything. Sosthenes, who is the eldest, will compose the lots: he has the right mind to evaluate well. You will agree on the choice, and I beg you, my children, out of my affection for you, not to quarrel in any way about these poor goods. It is better that one should yield to another a trifle than that the neighbors should witness a disunion between brothers, and resort to justice.

When the good man was dead and his sons had to think about the division, Sosthenes came and said to his brother,

– I am going to make the lots, as our father has ordered. But it seems right to me that I should choose the first one next, since I am five years your senior.

– This is justice itself, said Stephen, who had a confident heart. Make the lots and choose the first.

On this, Sosthenes seemed to think deeply. Our father, he said, owned two houses: the village house and the one in the woods. I will take the village house with its furniture and the land around it, and you will likewise take the house in the woods.

– Stephen remained seized with surprise. What the soldier jokingly called his house of the woods was only a hut for pecking birds, in the middle of a patch of sparse coppice that did not yield thirty-five sols in ten years. Of furniture it contained none, save a bundle of ferns to lie on, a lame bench, and a discarded pot.

– The stable houses two horned beasts, Sosthenes continued. I choose the cow and give you the goat. Out of six chickens, you will have three, and I think you are satisfied.

– But our father had money, said poor Stephen shyly. Don’t I have a right to it too?

– The elder didn’t dare say no, and his face grew longer as he dropped from a red woolen stocking a hundred beautiful, shiny gold coins. But there was a paper at the bottom of the stocking. And it was an acknowledgment from the King, for one hundred gold ecus precisely, due to the former soldier on his pay.

It was known in the country that the King never paid his debts, but had those who dared to claim them caned or hanged. Yet Sosthenes handed the paper to his younger son, and he shamelessly kept the ecus, declaring the division finished.

Stephan had tears in his eyes to see himself thus stripped, and especially to discover the bad heart of his brother whom he loved tenderly until then. He could have complained and demanded, but he remembered his father’s last words and did not want to disobey him.

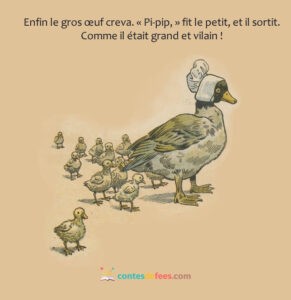

So he put his clothes in a bag and his three chickens in a basket, and was crossing the threshold when the house rooster suddenly flew across the yard and came to perch on his shoulder.

-“We had forgotten about the Jau,” said Sosthene (for that is what they call roosters in the village). Since there is only one, we have to cut it in half.

– Would you have the heart to kill this gentle beast, cried Sté phane, who follows us around like a dog and comes to eat at our fingertips? You may well offer it to me in addition to my share: it will not impoverish you so much.

– And why do you make this present to yourself? said the miser.

– So, keep it all, resumed Stephen. This Jau was loved by my father, who thought him funny in his ways and believed him to have enough malice to show off to a wizard. It will not be said that I had him butchered out of lust.

This arrangement pleased Sosthenes, but suddenly he changed his mind and grabbed the rooster by the legs.

– I see your cunning, he said to his brother. When you leave here you will go and complain about me, claiming that you have not received your full share of the inheritance. He armed himself with a large knife and split the rooster in two, from the crest and beak to the tip of the rump, so skillfully that there was not a feather’s difference between the two halves.

He tossed one to his brother, pushed him by the shoulders, and closed the door behind his back.

Then, returning to his well-furnished house, he made himself a stew with his half-cock and ate it all at supper.

Poor Stephen, confounded with sadness, went to his hut deep in the woods. When he arrived there, as he examined his half of Jau, he recognized that she was not quite dead, although it was quite close. And as he was a pitiful soul, he forgot his sorrows in caring for the miserable creature. Long nights were spent in vigil, long days in difficult dressings. The young man sold his best clothes to pay for jars of ointments, Mystic Elixir, and Samaritan Balm, but he persisted so well that he healed the Halfling of Jau.

As soon as Half of Jau was healed, he became great company for Stephen. He hopped on his one leg as fast as the three chickens ran, flapped his one wing, and sang with his half beak and half throat higher and clearer than he had in his life. He had also begun to speak, Sosthenes’ knife having cut his net, no doubt, or cut his tongue more slender, and it was then that his mind began to unfold. One saw him reasoning like a schoolmaster, arguing about everything and leaving the last word to nobody.

One day, while scraping the dust, he discovered four new pennies. This discovery made him think. Then he went to his master who was dreaming sadly in his hut, and he perched next to him on the cracked pot.

-“My master,” he said to him, “when you saved my life, you were not obliging an ingrate. Let us go together to the king and claim your hundred écus.

– Alas, my poor Half of Jau, said Stephen, to enter the King’s city, you must pay by passing the bridge.

– Bah, said the rooster, is that all? I have four pennies, I’ll pay for you. But, to hold my own there, I want a French-style blue suit, short breeches and tricorn hat.

The tailor in the village was a friend of my father’s, said Stephane. Maybe he will give you credit.

Half of Jau knew how to talk to the tailor and got dressed on credit. But the feather-maker did not want to hear anything, nor the passementier, nor the lingerie-maker. So that the plumet was missing from the hat, the ribbons in floquet from the garter, and the handkerchief in the pocket, which vexed the rooster cruelly.

– Let’s go, he said to his master. I don’t know how I’ll do it, but let me become a quarter Jau if I appear like this before the King.

Half Jau and his master left together early in the morning.

Stephen said goodbye to the goat, Half of Jau to his three hens. They recommended them to the neighbors and took to the meadows to gain the city of the King. Soon on their way, they found a small river: it reflected the blue sky and the green grass; it was charming to see, but it blocked their way. Half of Jau was not disconcerted. He took off his tricorn hat and motioned to Stephane to uncover himself as well.

– Good morning, Madame Rivière, he said politely. I am going to greet the King. Will you come with me?

– Good morning to you, honest people, replied the flattered River. I would gladly go to the King’s house, but the guards won’t let me in without money.

– Bah, said the rooster, is that all? Roll up your ribbon like a gallant floquet and come and tie yourself to my garter. I have four pennies: I’ll pay for them all.

The enchanted river didn’t let him tell her twice, and when the Halfling of Jau went back to his route, modest and stretching his paw, a flock of green and blue ribbon fell to his dewclaw.

A little farther on, the travelers entered a wooded country, but, as they wanted to cross a heathland, they saw that some peasants had lit it to clear it. The fire was coming to meet them and prevented them from passing.

Jau’s Half quickly pulled his hair, while his master imitated him.

– Good morning, Mr. Fire, he said. I’m going to say hello to the King.

– Will you come with me? ‘Good morning to you, honest people,’ Fire replied at once. I would visit the King, but his soldiers guard the gate.

-Bah!” said the rooster, “is that all? Ruffle your feathered flame and come plant yourself in my hat. I have four sous: I will pay for all. The fire did not beg, and the Half of Jau left proudly. He hopped beside his master and raised his head high to show off his plume.

Soon they saw the white towers and golden roofs of the city. But a great wind had risen that blew right in front of them, so strong that they could not move forward.

Stephane removed his cap. Half of Jau raised his tricorn hat and he said kindly:

– Good morning, Monsieur Vent. I am going to greet the King. Will you come with me?

– Good morning to you, honest people,” whistled Wind. I’d like to pay my respects to the King, but the palace guards are closing doors and windows in my face.

– Bah, said the rooster, is that all? Only fold yourself in quarters, like an elegant handkerchief, and nestle yourself in my pouch.

– I will bring you to the feet of the throne. When the well-folded wind had slipped into the pouch, Jau’s Halfling took three steps in front of his master, stretching his hock, raising his beak, and snorting. Never had one seen a more shimmering floquet than in her garter, a more flamboyant plume than in her blue hat, nor a handkerchief of finer fabric than that which came out of her pouch.

As he crossed the drawbridge into the capital, he proudly threw his four cents to the guards, then led his master to the palace.

– But the king’s doorman knew how to receive creditors. He had no sooner seen the IOU than he came across the bard hall laughing, and threatened to let the dogs loose.

-We’ll get nowhere that way, said the Halfling of Jau.

– Go to the inn, my master, and let me conduct your business.

Resting alone, the valiant rooster hopped around the royal castle on his one leg. Thus he arrived at the bailey and saw that a simple palisade enclosed them. Between the stakes, the slits were not wide enough to let the slimmest chicken through. But a flat half-Jau found the entrance sufficient.

So he snuck into the palace’s lower yard, and by chance he met the King there.

This prince loved fresh eggs so much that he deigned to unearth them himself. He brought home six of them that day in a fold of his ermine coat, and he looked cheerful. But he turned white with anger when the Halfling of Jau stood in his way to claim the hundred écus.

Extending his arm suddenly, he snatched the poor rooster by the wing.

– I’m going to put you in the spruce trees, he shouted angrily, and I’ll eat you on Sunday. What do you say, my friend?

– Nothing at all, made the Half of Jau, but I will remove the feather of my hat and let the Poppy cock me if you do not repent soon.

The King flung it into the hands of the basse-courier. ‘Stuff that piece of spruce chicken in me,’ he said, ‘and feed it to fatten up. I want to taste it in fricassee.

As soon as Jau’s Half saw himself locked up, he began to shout out loud:

– Fire! Fire! leave my blue hat, or I am a lost little chick!

The fire left the hat, snapping its flames. In a moment it had burned the door of the spruce trees, through which the Half of Jau came out, then it burned the chicken coops, the cowhouse, the porch, the sheepfold, from which all the livestock had to flee in haste. He was licking the walls of the palace when a hundred rushed valets finally succeeded in extinguishing him.

The rooster joined Stephen at the inn: he shared his supper with good appetite and spent the night on the foot of his bed. The next day, at noon, he slipped back into the palace’s backyard. When he found no one there, he climbed the back stairs and entered the dining room.

The King was at the table, on his dorseret chair, a large pate on his plate.

When the half-cock flew in front of him, in the middle of the dishes, he thought he would choke on his anger and grabbed him by the throat at once.

– You come for your master’s money, insolent bird, he said to him. What will you do if I throw you into this fire to flame you, to grill you, to reduce you to carbonade?

– Almost nothing, said Half Jau. I will untie the floquet of my garter, and may the Coquefague coquefredouille me if you do not suddenly repent.

– I am curious about it, said the King. And he threw it into the fireplace where more than ten faggots were burning, with flames to make one shudder.

But the Halfling of Jau shouted at the top of his voice: River, River! leave my garter, or I am a little lost chick! And the river, at once, unrolled its waves, which extinguished the fire, first, and filled with bubbling the dining room.

Everyone climbed onto the chairs, then onto the table, and the flood still rose. The king had climbed to the dorseret of his chair, but he could feel his legs in the water, and seeing the Half of Jau perched on the ledge, gazing down on all this tu multe, he begged him to retie his garter.

– I will retie it, said the rooster. But I want our hundred écus, or your daughter in marriage to my master.

– You shall have your hundred écus, said the King. Come tomorrow, you and your master. My treasurer will pay you back. Then the river flowed down the corridors, and the Jau came down proudly by the great staircase of honor, between all the chamberlains making the hedge.

Stephane couldn’t believe his ears when he heard that he would receive his due. He groomed the next day. Half Jau untucked his suit and dusted off his tricorn hat, and both went to the palace.

They were expected, and the doors opened wide for them. They were led to a terrace where the king was enthroned in ceremony with his daughter at his side and his entire court neatly arranged, drawing a perfect semicircle. But Half of Jau was worried because the Princess was crying. Turning his head, he discovered two prepared gallows: a large gallows to hang a man, and a small one next to it, of very good size for a rooster.

– Here you are in my hands, poor fragment of fowl, said the King, and your fool of a master with you. You shall see how I pay my debts. When we have you both hung by the collar, what will you find to defend yourself?

– Not much, said the Halfling of Jau. I’ll unfold the handkerchief from my pouch and let the Coquefredouille crack me, if you don’t see what you’ll see.

– Let’s see it then!” said the King.

The Princess, who had an honest soul and thought Stéphane looked good, had thrown herself on her knees before her father to beg him.

He pushed her aside with the end of his scepter and beckoned the executioners forward; but the Halfling of Jau cried:

– Wind! Mister Wind! unfold yourself quickly, or I’m all lost.

The wind unfolded at once, removed the two gallows and the whirling executioners, sent the major domes, the bailiffs, the soldiers, the great lords flying through the air, and was about to seize the King when he began to clamor:

– Fold up your handkerchief, Moitié de Jau, my treasurer will pay you.

The wind had not taken the treasurer away. The poor man approached shivering with a large bag of ecus. He began to count them, but the King did not have the courage to let him.

– Never have I paid my debts, he said. I can’t start at my age. I’d rather give my daughter’s hand.

The wind had not taken the King’s daughter away, and Stephen could see that she was pretty as a rose. He consulted with his eye as Jau’s half heart nodded his half head in consent, and he accepted without question. He and the Princess were married that very hour, and they lived happily ever after.

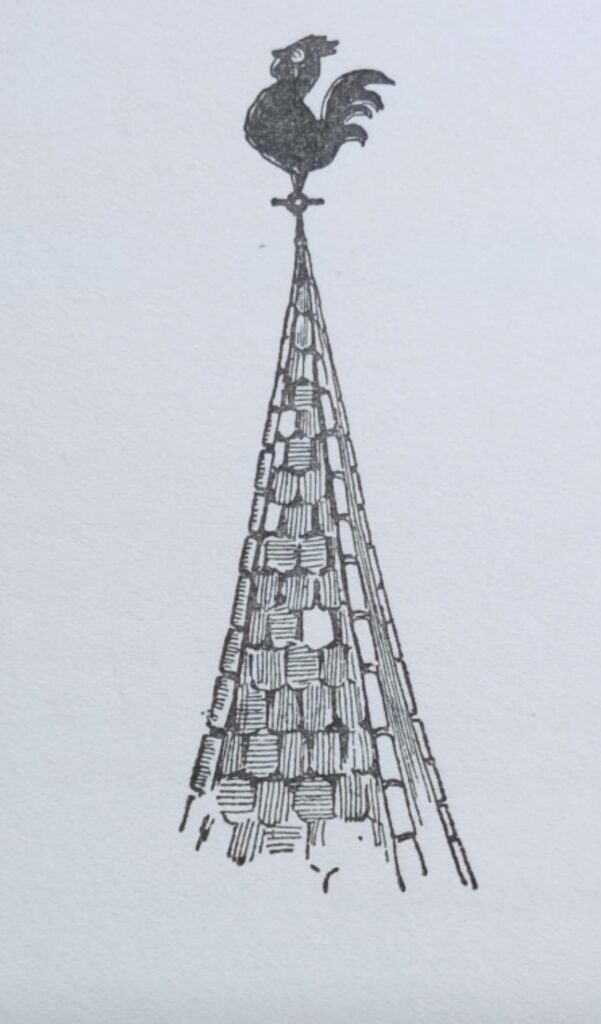

The wicked King was soon driven out by his people, and the soldier’s son ascended the throne. He was not ungrateful to the Halfling of Jau: he made him his minister, his intimate adviser, and, to honor him still more, he gave orders in his kingdom to place the image of the brave rooster, well chiseled, flat and gilded, on the top of the highest towers.

Since that time roosters have been put on the steeples.

Reprint of Tales of the Luisant Worm, written by Jeanne Roche-Mazon (1885-1953), illustrated by O’Klein (1893-1985 – With permission of the heirs)

Also read:

FIN

Vous avez repéré une erreur ? N’hésitez pas à nous la signaler en nous écrivant sur cette page

VOUS AVEZ AIMÉ CE CONTE? PARTAGEZ-LE!

AJOUTER AUX FAVORIS

Vous avez aimé ce conte? Ajoutez-le à vos favoris et donnez-lui un like en cliquant le coeur:

CATÉGORIES DU CONTE

Tout savoir sur les Contes de Fées

Avec les clés de lecture

Lisez notre page expliquant l’utilité des Contes de Fées, au niveau intellectuel, émotionnels et des valeurs morales.

Comprendre ce que représente chaque archétype de personnage, bon ou mauvais. L’importance des objets, de la magie, des animaux, etc.

Ajoutez votre version, votre audio ou vos images

Ou publiez votre propre conte

Envoyez-nous votre conte original, votre version ou complétez un conte avec vos illustrations ou un enregistrement audio.

Abonnez-vous à partir de 0,99€ (Promo)

Offre de lancement: Gratuit pour les professeurs

Écoutez les lectures audios en entier

Ajouter des bruitages et musiques de fonds

Garder vos contes favoris et gérer votre liste

Enregistrer vos histoires via l'enregistreur vocal

Accédez aux excercices de français en grammaire, compréhension, rédaction et débats

Télécharger les contes en PDF

Traduire les mots en anglais et améliorer votre français

D’AUTRES CONTES QUI POURRAIENT VOUS PLAIRE:

LE DICTACONTE (BETA)

Instructions

2) Réduisez l’enregistreur pour lire le conte en recliquant sur l’icône en bas de l’écran.

3) Éditez et sauvegardez en recliquant sur en bas.

C'est à vous de lire. Enregistrez-vous!

Vous devez être abonné(e) et connécté(e) pour pouvoir sauvegarder.

Connectez-vous – Abonnez-vous ou tester simplement

ABONNEZ-VOUS